Making a Living

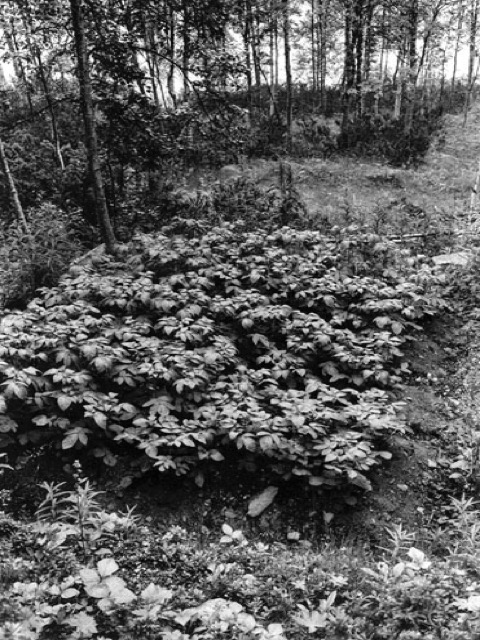

Potato patch, installation and text

Spare Time, Bildmuseet in Umeå, 2011

Link to website

A potato patch in the back yard can mean that survival throughout the year is secured, or that one has a meaningful and relaxed spare time. To grow potatoes has first and foremost been a way to contribute to the household sustenance, but today small scale farming can mean the opposite, that one has surplus for hobby activities.

Åsa Sonjasdotter’s project Making a Living consist of three parts: A potato patch large enough to feed a household over the winter; a text written for the occasion by artist Nicolas Siepen on human’s relation to sustenance and finally two art pieces borrowed from the Skellefteå Museum; a photograph by Henry Lundström and a wooden sculpture by Karl-Bertil Stenmark showing a couple working in their potato patch.

The potato patch was growing outside the museum entrance and was harvested by the end of the exhibition. The harvest was cooked and served by the patch.

Free as a bird in paradise

By Nicolas Siepen

When attempts are made – working on the basis of this time and the historic and geographical location – to differentiate nature and culture from one another, this is always done from the standpoint of culture. In other words, there is no untouched nature (any more)! The distinction as such is a cultural act, a form of contact, of cultivation. And people are the natural product whom this cultural distinction affects. In their extreme forms, nature, as distinct from culture, appears to be either idyllic, original and untouched (paradise) or wild, menacing and chaotic (hell). Correspondingly, human nature is either good, as in the natural state (so before culture), or evil because it has not been resolved by nature (animals), converted into culture and made civilized. The beautiful landscape provides the heavenly, ideal side of things, while natural disasters, the jungle represent the unpredictable, hostile side of nature. However, both sides are inseparably interwoven with one another; it all depends on the point from which one regards them and how closely one is exposed to nature, and in what situation. A jungle is a beautiful landscape as long as we do not have to battle our way through it. A natural disaster may be a sublime thing to watch, as long as we watch it on the television.

This form of contact could be called semiotic or aesthetic, as a precursor to designation and medialisation: nature as a landscape, a photograph or in general a picture. As a material process or matter in motion, nature can be merciless, deadly even. However, in the midst of material structures and flows, humans have learned how to assert themselves, and they will have developed culture by means of techniques in this permanent exchange. As matter, nature is not a landscape or a picture, but work and survival. No matter how much humanity believes, here and now, that it has liberated itself through technology, culture or civilization from its natural, material foundation, it has never succeeded in freeing itself entirely. Predefined basic qualities (respiration, energy, protection, nutrition, procreation, etc.) require the material underlying of nature in exchange. Apparently entirely artificial worlds such as major cities which in their inner nature can only be described as thoroughly cultivated (parks, zoos, etc.) are in reality undergoing a permanent exchange with a wild exterior.

The necessity of maintaining a regular nutritional intake has perhaps had the strongest influence on the development of cultural techniques which are supposedly unaffected by all forms of contact and even destruction. Three ways of making the land or the soil useful are known: hunters and collectors, livestock breeding and farming. The first requires a nomadic lifestyle, the second is on the threshold between nomadic conditions and settled conditions, and the third requires settled conditions.

Possession develops as a consequence of settled conditions: “The first person who surrounded a plot of land with a fence and came up with the idea of saying ‘this belongs to me’, and the people who found that it was sufficient simply to believe him, were the actual founders of civil society. How many crimes, wars, murders, how much misery and fear would humanity have been spared, had someone only torn out those fence posts and called to his fellow people: ‘Beware of listening to this imposter; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody’.” (Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men). One of the pioneers of the French Revolution and hence the worldwide triumphal march of the bourgeoisie, speaks here in the spirit and like a wise Indian chief or a moderner ecologist, and he does so with the idea of the good natural state at the back of his mind.

But do we still live on the earth, or rather on the economic processes set in motion by the said bourgeoisie as capitalism, on a gigantic body formed from streams of money?! The history of capital as a new dwelling for mankind implies something which Karl Marx called The Secret of Primitive Accumulation: “The so-called primitive accumulation (previous accumulation, according to Adam Smith), therefore, is nothing else than the historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production. It appears as primitive, because it forms the prehistoric stage of capital and of the mode of production corresponding with it. The economic structure of capitalist society has grown out of the economic structure of feudal society. The dissolution of the latter set free the elements of the former. The immediate producer, the labourer, could only dispose of his own person after he had ceased to be attached to the soil and ceased to be the slave, serf, or bondsman of another. […] In the history of primitive accumulation, all revolutions are epoch-making that act as levers for the capital class in course of formation; but, above all, those moments when great masses of men are suddenly and forcibly torn from their means of subsistence, and hurled as free and “unattached” proletarians on the labour-market. The expropriation of the agricultural producer, of the peasant, from the soil, is the basis of the whole process.”

In retrospect, the second half of the 20th century appears to be the historical moment in which mankind, on a massive, worldwide scale, wished repeatedly to flee work and possessions and indeed fled from them, and decided against the consequences of this primitive accumulation. This flight led to the country, into the forests, into the deserts, into the landscapes; and also into the pictures of nature. Cinema and photography have expressed these flights, and here it is possible to see how work, possessions, subsistence briefly followed culture out of the towns. In these pictures you see, nature appears fascinating and menacing as a landscape as it appears to be free from work, possessions and subsistence (contact), which it never is. The figures in the pictures are just recovering from work or have just started working. Free as a bird used to mean being released for shooting. There is no paradise!

Potato harvest and cooking at the last day of the exhibition.

Thanks to all participants. Photos by Mikael Lundgren/Bild i Norr

Vogelfrei im Paradies

Von Nicolas Siepen

Wenn versucht wird – von diesem Zeitpunkt und geschichtlich-geographischen Ort aus gesehen – Natur und Kultur voneinander zu unterscheiden, dann geschieht das immer aus der Perspektive der Kultur. Mit anderen Worten, es gibt keine unberührte Natur (mehr)! Die Unterscheidung als solche ist ein kultureller Akt, eine Form der Berührung, der Kultivierung. Und Menschen sind das Naturprodukt, dass diese kulturelle Unterscheidung trifft.

In ihren Extremen erscheint die von Kultur geschiedene Natur entweder als idyllisch, ursprünglich und unberührt (Paradies) oder als wild, bedrohlich und chaotisch (Hölle). Dem entsprechend ist die Natur des Menschen entweder gut, wenn sie sich im Naturzustand befindet (also vor der Kultur) oder böse, weil sie sich nicht von der Natur (vom Tier) gelöst hat und restlos in Kultur verwandelt und zivilisiert hat. Die schöne Landschaft bietet sich als die paradiesische, ideale Seite, die Naturkatastrophe, der Dschungel als die unberechenbare, feindliche Seite der Natur an. Beide Seiten sind jedoch unauflöslich miteinander verwoben, es kommt immer darauf an, von wo aus man sie betrachtet und wie nahe und in welcher Situation man der Natur ausgesetzt ist. Ein Dschungel ist eine schöne Landschaft, solange man sich nicht durch ihn durchschlagen muss. Eine Naturkatastrophe kann ein erhabenes Schauspiel sein, solange man es am Fernseher verfolgt.

Diese Form der Berührung könnte man die semiotische oder ästhetische nenne, als Vorgang der Bezeichnung und Medialisierung: die Natur als Landschaft, Photographie oder allgemein Bild. Als materieller Prozess oder Materie in Bewegung kann Natur unerbittlich, gar tödlich sein. Menschen haben sich jedoch inmitten von materiellen Strukturen und Strömen behaupten gelernt und in diesem permanenten Austausch sollen sie mittels Techniken Kultur entwickelt haben. Als Materie ist Natur keine Landschaft oder Bild, sondern Arbeit und Überleben. Egal wie weit sich die Menschheit hier und jetzt via Technik, Kultur oder Zivilisation von ihrer natürlichen, materiellen Basis emanzipiert zu haben glaubt, ihr ist es nie gelungen sich völlig frei zu machen. Bestimmte Grundeigenschaften (Atmung, Energie, Schutz, Nahrung, Fortpflanzung etc.) erfordern den materiellen Naturbezug als Austausch. Scheinbar völlig künstliche Welten wie Großstädte, die in ihrem Inneren Natur nur als durch und durch kultiviert zulassen (Parks, Zoos etc.) befinden sich in Wirklichkeit in einem permanenten Austausch mit einem wilden Außen.

Die Notwendigkeit regelmäßig Nahrung zu sich zu nehmen hat vielleicht den stärksten Einfluss auf die Entwicklung von Kulturtechniken ausgeübt, die allesamt Formen der Berührung und auch Zerstörung von etwas vermeintlich unberührten sind. Drei Formen sich das Land oder die Erde nützlich zu machen sind bekannt: Jäger und Sammler, Viehzucht, Ackerbau. Ersteres setzt eine nomadische Lebensform voraus, die Zweite befindet sich an der Schwellen zwischen nomadisieren und Sesshaftigkeit und die Dritte setzt Sesshaftigkeit voraus. Besitz entwickelt sich als Folge von Sesshaftigkeit: “Der erste, der ein Stück Land mit einem Zaun umgab und auf den Gedanken kam zu sagen »Dies gehört mir« und der Leute fand, die einfältig genug waren, ihm zu glauben, war der eigentliche Begründer der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft. Wie viele Verbrechen, Kriege, Morde, wie viel Elend und Schrecken wäre dem Menschengeschlecht erspart geblieben, wenn jemand die Pfähle ausgerissen und seinen Mitmenschen zugerufen hätte: »Hütet euch, dem Betrüger Glauben zu schenken; ihr seid verloren, wenn ihr vergesst, dass zwar die Früchte allen, aber die Erde niemandem gehört«.” (Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Abhandlung über den Ursprung und die Grundlagen der Ungleichheit unter den Menschen). Einer der Wegbereiter der Französischen Revolution und damit dem weltweiten Siegeszug der Bourgeoisie spricht hier dem Geiste nach wie ein weiser Indianer Häuptling oder ein moderner Ökologe und er tut das mit der Idee des guten Naturzustandes im Hinterkopf.

Aber leben wir heute noch auf der Erde oder nicht vielmehr auf den von besagter Bourgeoisie als Kapitalismus in Gang gesetzten ökonomischen Vorgängen, auf einem gigantischen Körper, der aus Strömen von Geld gebildet wird?! Die Geschichte des Kapitals, als neue Wohnstätte der Menschen setzt etwas voraus das Karl Marx Das Geheimnis der ursprünglichen Akkumulation genannt hat: „Die sogenannte ursprüngliche Akkumulation (previous accumulation bei Adam Smith) ist also nichts als der historische Scheidungsprozess von Produzent und Produktionsmittel. Er erscheint als ursprünglich, weil er die Vorgeschichte des Kapitals und der ihm entsprechenden Produktionsweise bildet. Die ökonomische Struktur der kapitalistischen Gesellschaft ist hervorgegangen aus der ökonomischen Struktur der feudalen Gesellschaft. Die Auflösung dieser hat die Elemente jener freigesetzt. Der unmittelbare Produzent, der Arbeiter, konnte erst dann über seine Person verfügen, nachdem er aufgehört hatte, an die Scholle gefesselt und einer andern Person leibeigen oder hörig zu sein. […] Historisch epochemachend in der Geschichte der ursprünglichen Akkumulation sind alle Umwälzungen, die der sich bildenden Kapitalistenklasse als Hebel dienen; vor allem aber die Momente, worin große Menschenmassen plötzlich und gewaltsam von ihren Subsistenz Mitteln losgerissen und als vogelfreie Proletarier auf den Arbeitsmarkt geschleudert werden. Die Expropriation des ländlichen Produzenten, des Bauern, von Grund und Boden bildet die Grundlage des ganzen Prozesses.“

Die zweite Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts erscheinen rückwirkend als der historischen Moment im dem Menschen zum wiederholten male massenhaft und weltweit der Arbeit und dem Besitz entfliehen wollten und auch entflohen sind und sich gegen die Folgen dieser ursprünglichen Akkumulation gestemmt haben. Diese Flucht führte aufs Land, in die Wälder, die Wüsten und in die Landschaften also auch in die Bilder der Natur. Das Kino und die Photographie haben den Fluchten Ausdruck gegeben und hier kann man sehen, wie ihnen die Arbeit, der Besitz, die Subsistenz kurz die Kultur aus den Städten gefolgt ist. In diesen gelebten Bildern erscheint die Natur als Landschaft faszinierend und bedrohlich, weil sie eben von der Arbeit, Besitz und Subsistenz (Berührung) befreit scheinen, was sie jedoch nie sind. Die Figuren in den Bildern erholen sich nur von der Arbeit oder haben bereits wieder damit begonnen. Vogelfrei hieß ja auch immer zum Abschuss freigegeben zu sein. Es gibt kein Paradies!

Fågelfri i paradiset

av Nicolas Siepen

Fågelfri i paradiset. Om man i vår tid och med dess historisk-geografiska utgångspunkt försöker skilja naturen från kulturen så sker detta alltid ur kulturens perspektiv. Med andra ord, det finns ingen orörd natur (längre)! Åtskillnaden i sig är en kulturell akt, ett kontaktskapande, en form av kultivering. Och människor är naturprodukten som drabbas av denna kulturella åtskillnad. I sina extremer framstår den från kulturen skilda naturen antingen som idyll, ursprunglig och oberörd (paradis) eller som vild, hotfull och kaotisk (helvete). Som en följd av detta är människans natur antingen god, när den befinner sig i naturtillståndet (alltså innan kulturens inträde) eller ond eftersom den inte har löst sig från naturen (från djuret) och inte helt och hållet förvandlats till kultur och blivit civiliserad. Det vackra landskapet kan ses som den paradisiska, ideala sidan av naturen medan naturkatastrofen, djungeln kan ses som den oberäkneliga, fientliga sidan. Båda sidor är dock oupplösligt sammanvävda. Det beror alltid på varifrån man betraktar och hur nära och i vilken situation man utsätts för naturen. Djungeln är ett vackert landskap så länge man inte är tvungen att slå sig igenom den. En naturkatastrof kan vara ett storslaget skådespel så länge man kan betrakta det på tv.

Denna form för kontakt skulle man kunna kalla den semiotiska eller estetiska, eller beteckningens och medialiseringens process: Naturen som landskap, fotografi eller allmän bild. Som materiell

process eller materie i rörelse kan natur vara obeveklig, till och med dödlig. Människor har emellertid lärt att hävda sig mitt bland dessa materiella strukturer och strömmar och i det fortlöpande utbytet har kulturen utvecklats, sägs det, med hjälp av teknik. Naturens grundval är därför varken landskap eller bild utan arbete och överlevnad. Oavsett hur mycket mänskligheten här och nu tror sig ha blivit frigjord med hjälp av teknik, kultur och civilisation, har den aldrig lyckats göra sig helt fri från sin naturliga, materiella bas. Mänskliga grundfunktioner (andning, energi, skydd, föda,

fortplantning mm) kräver den materiella referensen till naturen för utbyte. Till synes helt konstgjorda världar som t.ex. storstäder där naturen bara tillåts i form av kultiverade parker eller djurparker

ingår i verkligheten i ett permanent utbyte med det okultiverade. Nödvändigheten i att få föda

regelbundet har antagligen utgjort det största inflytandet på utvecklingen av olika kulturtekniker som alla är former av beröring men också förstörelse av något som är förment oberört.

Det finns tre kända former genom vilka mänskligheten har brukat jorden: Jagande och samlande, boskapsskötsel och jordbruk. Den första formen kräver en nomadiserande livsform, den andra är i övergång mellan en nomadiserande och en bofast livsform och den tredje kräver en bofast livsform.Ägandet har utvecklats som en följd av den bofasta livsformen: ”Den förste som satte ett staket kring ett landområde och som kom på tanken att säga: ’Detta tillhör mig’ och som hittade folk som var primitiva nog att tro på honom, var egentligen grundaren av det borgerliga samhället. Hur många förbrytelser, krig, mord, hur mycket elände och förskräckelse skulle mänskligheten besparats om någon skulle ha rivit staketet och ropat till sina medmänniskor: ’Akta er för att lita på bedragaren; ni är förlorade när ni glömmer att skörden tillhör alla men marken tillhör ingen’.” (Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Avhandling om ursprunget och orsakerna till ojämlikheten mellan människorna). En av dem som beredde vägen för den franska revolutionen och bourgeoisiens segertåg över hela världen talar här som vore han en vis indianhövding eller en modern ekolog och han gör det med idén om det goda naturtillståndet i åtanke.

Men lever vi idag fortfarande på jorden eller inte snarare på ekonomiska processer, igångsatta

genom bourgeoisiens kapitalism, på en gigantisk kropp som bildas av penningflöden?! Historien om kapitalet, människornas nya boning förutsätter något som Karl Marx nämnde i Den ursprungliga

ackumulationens hemlighet (Kapitalet, Tjugofjärde kapitlet): ”Den s.k. ursprungliga ackumulationen är alltså ingenting annat än den historiska skiljeprocessen från producent och produktionsmedel. Den framstår som ursprunglig eftersom den bildar kapitalets förhistoriska tid och dess motsvarande produktionssätt. Det kapitalistiska samhällets ekonomiska struktur har framsprungit ur det feodala samhällets ekonomiska struktur. Upplösningen av den förre har frigjort element av den senare. Den omedelbara producenten, arbetaren, kunde först förfoga över sin egen person när han hade slutat att vara bunden till jorden och att vara en annan persons slav eller livegen […] Epokgörande i historien om den ursprungliga ackumulationen är alla omvälvningar som tjänar som hävstång för den kapitalistklass som skulle bildas; men framför allt de ögonblick där stora människomassor plötsligt och våldsamt slits från sitt levebröd och kastas som fågelfria proletärer på arbetsmarknaden. Grundläggande för hela processen är exproprieringen av jordbrukets producenter, av bönderna som fick gå från sin jord.”

När man ser tillbaka så framstår andra halvan av 1900-talet som det historiska tillfälle då människor över hela världen upprepade gånger försökte och ibland också lyckades undfly arbete och privat ägande och där man kämpade emot följderna av den ursprungliga ackumulationen. Flykten ledde ibland även tillbaka landsbygden, till skogarna, till öknarna och in i landskapen, alltså in i naturens bilder. I filmer och fotografier som beskriver denna flykt kan man se hur arbetet, ägodelarna och levebrödet, kort sagt kulturen har följt dem från städerna. I dessa bilder ser man hur naturen framstår som ett fascinerande och hotfullt landskap till synes befriad från arbetet, ägodelarna och levebrödet, vilket den aldrig kommer att bli. Personerna i bilderna vilar bara från arbetet eller har kanske redan börjat arbeta igen. Att vara fågelfri innebär också att alltid vara fredlös. Det finns inget paradis!